We are often told that people should not ‘live beyond their means’, that is, that no individual person, nor any corporate entity like a business or a government, should spend more money during a given period than they take in as income or as revenue. Doing so is judged to be profligate, irresponsible, and only setting oneself up for pain in the long run. For countless centuries, if not millennia, the balanced ‘budget’ has been regarded as the sine qua non of fiscal prudence and ‘sound’ finance.

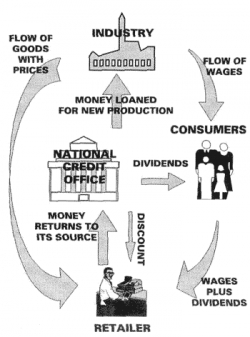

And yet, if we look at our economies over any given period of time, it is quite normal for individual consumers, considered in the aggregate, to spend more than they receive in income, for governments at all levels to spend more than they take in viataxes, and even for businesses, considered again as a whole, to spend more money (thanks to long-term capital investments), than they simultaneously receive as revenue. How can this be? How can we explain the conflict between the common theory (i.e., what should be the case: balanced budgets) and what we observe as a fact in the real world (i.e., unbalanced budgets)? Is it the general tendency of human beings to be congenital spendthrifts? Are humans innately vicious when it comes to the getting and spending of money?

Quite irrespective of such questions concerning human nature, there is actually a technical economic reason why consumers, governments, and business typically spend, in the aggregate, more money than they receive and do not, therefore, ‘enjoy' balanced budgets.